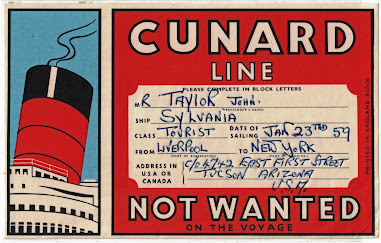

RMS Sylvania, on the left, at the Liverpool Dock. We entered the ship by the rear gangway. We were travelling tourist class, and our cabin was the last one on A Deck, at the stern of the ship, on the port side, somewhere near the propellers. Anyone who has crossed the North Atlantic in winter will know this is not a good place to be. Situated at one end of the vessel, about as far from midship as you can get, magnifies the effects of pitch in a rough sea. As we soon learned, the Atlantic was in a ferocious mood. Two days out, it seemed as if we were sailing to stand still, with waves and spume inundating the foredeck as we crashed through a roiling ocean. Our voyage had become a nautical seesaw.  My father plotted our route, annotating the storm as v/rough

My father went to sea at the age of 14. His baptism into the rigours of war began in 1940, when he served as a deckhand on a Manchester Ship Canal tugboat. This involved being dispatched into the Irish Sea to tow damaged Liberty Ships, loaded with vital supplies, to the safety of port. He was accustomed to the effects of foul weather and heavy seas, which was all too evident when the ship's dining room opened for breakfast. He was one of only a handful of passengers who still had an appetite, and was given a carte blanche by the waiters. His enthusiasm meant that I was taken -- ashen-faced -- to see the atomizing effects of gale-force wind on the crests of sea-swell, which was followed by an excursion into the 'bowels' of the ship, where it was pointed out that we were now well below the waterline. My mother, by comparison, spent almost the entire voyage in bed, suffering from seasickness, and comforted by daily visits from the ship's nurse who plied her with dry toast and Canada Dry ginger ale.

My mother was evacuated at the outset of World War II, but her parents, lulled into a false sense of security during the 'phoney war' period, brought her back home to Salford just in time for the Christmas Blitz of 1940. Toward the close of the following year, she started work at a garment factory in Manchester. There, she was trained as a seamstress, cutter and designer, specializing in manufacturing clothing for people displaced by the war. It is no exaggeration to say that there was nothing my mother couldn't make (or deconstruct and remake), whether it was formal suits, men's shirts, dresses cut on the bias, baby clothes, wedding dresses, and even custom-made drapery. There is only one photograph that survives of our voyage to America. It is of my mother, standing on deck as we approached Halifax, Nova Scotia. She is wearing a coat she had made from a blanket. Times were hard, but my parents were harder.

My parents decided to emigrate for a convergence of reasons. First, my father, at the time an impressionable youth, was fascinated with America. During the war, he had encountered many American merchant mariners, who kindly gave him clothes, records and foodstuffs, among which were oranges, much-prized and rarely seen. Dressed in his American gear earned him the epithet "Yank". The records were gold-dust to him, as he was passionate about the "big bands": Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Les Elgart, Gerry Mulligan, Stan Kenton and the like. There was no such thing as a 'bucket list" in the 1950's, but near the top of my father's ambitions was to see the Golden Gate Bridge. After the war, our country entered what historians now call the "Age of Austerity". Essentially, Britain was broke and battered, and its imperial days over. While we may not have won the war, we hadn't lost it either, but the victory we celebrated was Pyrrhic. My parents married in 1949, and spent the next five years on a council-house waiting list due to a scarcity of housing. During our wait, we were living in the front parlour of my grandparents' terraced house, with no hot water, no bath, a shared kitchen and an outside toilet. Meat and other foods were rationed until 1954. Petrol rationing was reintroduced in

The wireless and phonograph in the parlour

1956. There is no nostalgia for the good old days here. Then, my mother's sister married a G.I. He was a master sergeant in the US Air Force, a mechanic in the Strategic Air Command, whose speciality was B-52 bombers. He had been stationed at RAF Burtonwood, near Warrington, but, around 1957, he was transferred to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base outside Tucson, Arizona. Encouraging letters and promises of a better life started arriving from my aunt. They were food for thought. Thanks to the sooty emissions of factory chimneys and coal fires, I coughed my way through early childhood until the family doctor said to my mother, "What this child needs is a warm, dry climate". It was a fateful statement. Few places are hotter and drier than Tucson, Arizona. Alea iacta est.

An artefact of the "Age of Austerity"

One of my earliest memories of the journey was sailing into Cobh Harbour, and seeing the spire of the Cathedral of St. Colman towering over the city. The liner didn't dock, but anchored offshore, and was serviced by a packet boat that delivered more emigrants and mail bound for the Irish diaspora living in New York, Boston and beyond. We were not allowed to disembark, but some locals came on board, taking the opportunity to sell souvenir harp brooches inlaid with green enamel, shamrock lapel badges and an assortment of embroidered linen goods. In our complete ignorance of the Irish language, its place name was reduced to 'Cob'. It was my first introduction to Ireland, albeit a brief one. Little did I realize at the time, that 58 years later, I would be taking up residence there.

Cunard ships had been sailing from Liverpool to New York since 1840, when Samuel Cunard won a trans-Atlantic mail contract. The ship's prefix, RMS, Royal Mail Ship, speaks to his business acumen. Cobh became a port-of-call in 1859, and remained so until the end of the service. The RMS Sylvania was built at Clydebank in 1957, and was the last Cunard liner built specifically for regular trans-Atlantic traffic. Her last voyage as part of the Liverpool to New York service was made on the 24th of November, 1966. However, she made a final one-off voyage on the 30th of November, 1967; coincidentally, on my birthday. Much of the ship's interior, despite the fact that the bulk of the passengers were tourist class, was tastefully elegant. I remember distinctly her cinema, complete with a balcony, and being mesmerized by Walt Disney's Fantasia in colour. The film was first released in 1940, but Cunard was showing a recently enhanced version, reissued with stereo sound and in widescreen SuperScope.

In the lounge, there were writing desks, supplied with Cunard's headed airmail and bond paper, postcards and envelopes. I wrote to my grandmother against a backdrop of Perry Como's Magic Moments. Our cabin had a port hole and two beds, a sink, but no ensuite toilet, and it cost the princely sum of £570 (about £1,930 pounds in 2020).

Samuel Cunard, from a family of Quaker Loyalists, was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and established the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company in 1839. From this venture, his maritime commercial interests eventually morphed into the Cunard Line. I knew none of this when we disembarked at his birthplace. We were allowed a few hours to explore the city, of which I remember nothing, because I was completely distracted by the discovery that I had developed 'sea legs', the body's natural reaction to experiencing the continual pitch and yaw of a ship at sea.

There was much excitement aboard ship as we approached our destination. I was standing on the deck, clutching the railing, and wearing a grey ushanka against the cold. We had cleared the Verrazzano Narrows, unspanned, as the suspension bridge had yet to be built, and had entered the Upper Bay, sailing along the boundary between New Jersey and New York. From the port side, we watched the Statue of Liberty, the 'Mother of Exiles', slide past. Dead ahead, the skyline of Manhattan loomed as tugboats escorted the ship up the Hudson River to berth at New York's Passenger Terminal, Pier 92. The terminal is surrounded by a forest of skyscrapers. In 1959, with little comparanda in the world, it was a truly awesome sight to behold.

New York Passenger Terminal on the Hudson River

The voyage took six days, and we had travelled some 5500 kilometers, but there was still a continent to cross. There was an undeniable frisson of excitement and adventure to all of this, though my parents must have been anxious. Ahead were prospects: new vistas, new opportunities, a new and different lifestyle. Looking back at events, now over sixty years ago, there were also unexpected consequences. I was too young then to appreciate that I would always be a 'foreigner', not just in America but in my own country too. Over time, you adapt to new surroundings, adopt new customs and reinvent yourself. You end up 'different', shaped by those 'new experiences' not shared by those you left behind. They change too. Everything is in a state of flux. The city we left is no longer, demolished and rebuilt beyond all recognition, transformed into a modern metropolis of glass and chrome. It is an alien landscape. 'Home' has been relegated to memory, a construct.

Salford Quays

The Sylvania has gone too, along with my travelling companions: all have slipped quietly into history. And the lyrics sung by Perry Como echo: Time can't erase the memory of

These magic moments filled with love

If only it were so.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment