|

4348 Lt. John Thomas Cox, D.C.M. |

Around the time Anthony Cox was born on the 16th of October 1859, the village of Curraglass, his birthplace, was home to about 260 people. It is described in the Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1849) as:

Curriglass [i], a

village, in the parish of Mogealy, Union of Fermoy, Barony of Kinnataloon, County

of Cork, and province of Munster. … This village is situated in the fertile

vale of the Bride … it consists of a short street extending nearly east and

west, with another branching from it towards the south. The parochial church, a

small but neat structure with a square tower, is near the east end of the

village. In the vicinity are numerous gentlemen's seats, embosomed in finely

wooded demesnes.

There is a folk song, How Many Miles to Curriglass, which was composed well before Ireland became compliant to European standards of metrification. If you are standing on the border between Cork

and Waterford, the answer would be ‘about three quarters of a mile’. Double

that distance and you are in the nearby market town of Tallow.

|

| The Plough Inn, Curraglass, circa 1910 It stands on the corner of the T-Jjunction described above source: Conna History click on images to enlarge |

We don’t know whether

Anthony’s father, Thomas Cox, was a native of the village, or had moved there

from another part of County Cork, but he lived there until his death in 1901.

Thomas married Mary Neville in the parish of Conna, in which Curraglass lies,

on the 23rd of September 1849. Thomas and his children were Irish speakers.

Anthony is their oldest known child, but he was born ten years after his parents were married. There are no doubt older siblings. His younger brothers are William (born abt. 1860); Richard (1863); Thomas (1864); James (1866); John (Jack) of uncertain birthdate, and Philip (1871). His sister, Mary, was born in 1861.

|

| Conna Parish Records: Marriage of Thomas Cox and May Neville |

Anthony is their oldest known child, but he was born ten years after his parents were married. There are no doubt older siblings. His younger brothers are William (born abt. 1860); Richard (1863); Thomas (1864); James (1866); John (Jack) of uncertain birthdate, and Philip (1871). His sister, Mary, was born in 1861.

Anthony’s father was a

tailor. William, Richard, and Philip joined the family business and remained in

Tallow and Ballynoe. James and Mary emigrated to England, and Thomas migrated to New York. John moved to San Diego, California. In 1891, Anthony is found working in a chemist

shop in Doneraile, Co. Cork, where he met Mary Joyce. They were married on the 28th

of November 1891. Two years later, they had moved and were living at 4 Jackson's Terrace in Ballintemple, Cork City, where Mary delivered their first child, Mary Bridget Cox,

on the 1st of February 1893. Anthony found a new job as a

groom. Shortly after, they moved to 2 Walsh’s Place on Leitrim Street.

Leitrim Street is situated

north of the River Lee in a bustling area called Blackpool, a name synonymous

with industry and its legions of working men and women. Walsh’s Place was just around the corner from

James J. Murphy’s Lady’s Well Brewery and a busy warehouse of the Cork Distilleries Company. Across the street

was Cornelius O’Connell’s thriving timber business, and, a few doors away,

Spillane’s Salt and Lime Works. It was

only on a quiet Sunday morning that the bold notes of nearby Shandon Bells were

able to soar above the din. In a way, it

was fitting for a groom to move into Walsh’s Place. It had been built around the

middle of the nineteenth century as a carriage house, but, by the time the Cox

family moved in, the horses had long gone from its yard, being replaced with a

dense cluster of modest cottages [ii]. It was

at number 2 that John Thomas Cox was born on the 13th of April 1894. It seemed like a

quiet time to be born, but, as it turned out, a potentially dangerous one.

|

| Entry of the birth for John Thomas Cox in the Civil Records |

John was only a boy when

his parents left Cork for Midleton, a handsome market town situated mid-way

between Cork and Youghal, as its name implies. Anthony found employment as a

coachman and domestic servant, and sired a third child, William Cox, who

arrived on the 2nd of December 1896. The family initially rented a

cottage at 2 Darby's Lane, and then moved to 1 Dickinson’s Lane in the town

centre. John was

educated at the Midleton Christian Brothers School, where he was taught Irish. He and his family were

Roman Catholic. Upon leaving school, he secured a job as a clerk in a firm of

local solicitors.[iii] Conditions for the

Cox family were improving, and, in 1914, Midleton looked like a film set for an

idyllic Edwardian town.

|

| Midleton on the eve of World War I source |

Apocalypse Now

Then the world changed,

and it would never be the same again. The First World War and its aftermath were profoundly

cataclysmic. The growing pressures of European geopolitics erupted like hot

magma from a volcano, and, by the time the fighting was over, millions lay

dead, monarchies and their empires had collapsed, social change was unleashed,

new ideologies struggled to fill the political vacuum, and the seeds of modernity were sown. The Irish seized the opportunity

of a distracted Britain and revived their struggle for self-determination in

the Easter Rising of 1916, which led to independence from the United Kingdom and vicious civil war.

The First World War started in August 1914 as the German

army swept through Belgium and into France. The British Expeditionary Force -- the Old Contemptibles -- was dispatched quickly to check the enemy's advance. It was just as quickly wiped

out. Fresh recruits were needed; first through persuasion, then, desperately, through

conscription. Ireland was spared the rigours of compulsory service, though some 140,000 volunteers willingly enlisted, not a few induced by Redmond's promise of Home Rule, others out of economic necessity. Herbert Kitchener, one of Britain's chief agents of imperialism in Africa and India, was appointed Secretary of State for War in 1914, and was given the task of raising a new army, which was divided into army groups.

John Thomas Cox enlisted in September 1914, travelling to Fermoy (New Barracks) to join the newly formed 6th (Service) Battalion of the Connaught Rangers. [iv] The Rangers, referred to by the Duke of Wellington as The Devil's Own, was an infantry regiment of the line, which began its career as the 88th Regiment of Foot. It was raised in Connaught during 1793 in response to the French Revolutionary Wars, and merged with the 94th Regiment of Foot in 1881 to become the 1st and 2nd Battalions Connaught Rangers respectively. The regiment fought in the Napoleonic, Crimean and Boer Wars, and was one of the first regiments to arrive on the Western Front. The Daily Mail's chief war correspondent, George Curnock, watched the 2nd Connaught Rangers march passed the Metropole Hotel in Boulogne on the 13th of August 1914. They were singing It's a Long Way to Tipperary, a favourite born out of their fondness for Tipperary Town where they had been stationed. His report, published on the 18th, was cabled all over the world, which helped to make the song an overnight sensation. The recording made by the Irish tenor, John McCormack, in Novermber 1914, turned it into the unofficial anthem of the war. [iv]

John Thomas Cox enlisted in September 1914, travelling to Fermoy (New Barracks) to join the newly formed 6th (Service) Battalion of the Connaught Rangers. [iv] The Rangers, referred to by the Duke of Wellington as The Devil's Own, was an infantry regiment of the line, which began its career as the 88th Regiment of Foot. It was raised in Connaught during 1793 in response to the French Revolutionary Wars, and merged with the 94th Regiment of Foot in 1881 to become the 1st and 2nd Battalions Connaught Rangers respectively. The regiment fought in the Napoleonic, Crimean and Boer Wars, and was one of the first regiments to arrive on the Western Front. The Daily Mail's chief war correspondent, George Curnock, watched the 2nd Connaught Rangers march passed the Metropole Hotel in Boulogne on the 13th of August 1914. They were singing It's a Long Way to Tipperary, a favourite born out of their fondness for Tipperary Town where they had been stationed. His report, published on the 18th, was cabled all over the world, which helped to make the song an overnight sensation. The recording made by the Irish tenor, John McCormack, in Novermber 1914, turned it into the unofficial anthem of the war. [iv]

|

| Melbourne. Weekly Times 22 Aug 1914:30 |

|

| Kilworth Camp |

The 6th Connaught Rangers was part of Kitchener's New Army, and belonged to Army Group K2. It was assigned to the 47th Brigade of the 16th Irish Division. The battalion was raised at Kilworth Camp, Co. Cork, soon after war was declared, and placed under the command of Lt. Col. Lenox-Conyngham. It received training at (Lynch Camp) Kilworth, and at Moore Park, Fermoy, before being sent to Blackdown Camp, near Aldershot, in England for more intensive training in September 1915. John Thomas Cox and his battalion then sailed from Southampton to Le Havre, arriving at 6:00 in the morning of the 18th of December. The next day, they were transported by train to Hesdigneul-lès-Béthune (Pas-de-Calais), a once quiet farming village, but now close enough to the front to hear the guns. Here they would spend their time becoming 'acclimatized', as drafts of men joined working parties, spent some time in the trenches for instructional purposes, and wondered what their first Christmas would be like in a war zone, and would it be their last.

|

| rue de la République, 1914: source |

|

| Loos - Hulluch Sector |

Since, they were not seasoned troops, the 6th Battalion was apprenticed to the 46th Infantry Brigade, part of the 15th (Scottish) Division, and were moved to the front in the Loos salient on the 26th of January 1916. The following day, the battalion established its headquarters at Philosophe, and the Connaught Rangers came under artillery fire and repulsed an enemy attack. The artillery barrage intensified on the 28th, and two men were killed, the battalion's first losses of the war. On the 1st of March, the 16th Irish Division was made operational, and joined I Corps, commanded by Sir Hubert Gough, an officer who described himself as "Irish by blood and upbringing". While the Easter Rising was taking place in Ireland, the 16th Irish Division was subjected to an agonizing gas attack around Hulluch.[v] In the ensuing months, the 6th Battalion did their part in holding the line in the Loos sector at a cost of 417 dead. On the 24th of August, they were pulled from the line, rested, and augmented with a draft of 96 men. Five days later, the battalion boarded a train and moved southward toward the Somme to face Guillemont, a modest farming village. The period of initiation was over. In the following days, their training, courage and spirit would be put to the test on the battlefields of the Somme.

The Battle of Guillemont

|

| Troops moving up to Guillemont: source |

Guillemont, was well-fortified with underground tunnels and concrete emplacements. It had already been attacked by British and French forces on eight separate occasions, all of which had failed miserably. Now it was the turn of the 16th Irish Division. As the photograph above shows, it had been raining heavily, and, before the scheduled assault at midday on the 3rd of September, intense enemy shelling had turned the area into a mire and killed nearly 200 men of John's battalion. Then, the wailing skirl of the pipes signaled zero hour, and the 6th Connaught Rangers, 6th Royal Irish and 7th Leinsters, went over the top. The much-admired Jack Lenox-Conygham, commanding the 6th Battalion, stood on the parapet with a walking stick in one hand and a pistol in the other, and beckoned his troops forward. It was his final act as a bullet ripped threw his forehead.

As if from the days of Cú Chulainn, the lon laith, the flame of valour, rose up within each Irishman. There would be fury and hell to pay. At a speed that shocked, the morass of no man's land was crossed, the enemy's frontline positions were overwhelmed, as was their second line, and their third.[vi] Private Thomas Hughes of the 6th Connaught Rangers, already wounded four times during the attack, charged and captured a German machine-gun, killed its gunners, and took four prisoners back to his lines. He was awarded a Victoria Cross. The English troops fighting on their right flank reported that they had never seen such determination, and described the Irish assault as a 'human avalanche'! The press reported it as one of the most astonishing feats of the war. All of this had been accomplished at short notice. The 47th Brigade had only been given the order to attack during the afternoon of the day before. After the battle, the rain returned to cleanse the ruins of the bloodstained village.

|

| Irish troops overwhelm German positions at the Battle of Guillemont Illustrated London News 7 Oct 1916:418-19 |

"...a hotblooded Irishman is a dangerous customer when he gets behind a bayonet..."

Father Willie Doyle SJ

Battle of Ginchy

Father Willie Doyle SJ

Battle of Ginchy

Under normal conditions, the rural village of Ginchy is about a twenty minute stroll northward from Guillemont, but, in 1916, normality had been suspended. Ginchy had been transformed into a well-fortified stronghold. The village occupied strategically high ground, making it an ideal observation post for directing the fire of German artillery. From the 3rd to the 7th of September, all attempts by the 7th Division to captured Ginchy were repulsed with heavy losses. It was proving to be a tough nut to crack. On the night of the 7th of September, as the weather deteriorated, the 7th Division was replaced by the already tired and depleted 16th Irish Division. Reviewing the task before them, Lieutenant Arthur Young of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, asked his batman:

"Well, O'Brien, how do you think we'll fare?"Miraculously, both survived, but only after fierce fighting. At 4.45pm, on the 9th of September, the order was given to attack the heights of Ginchy. The 48th Brigade was on the left. The 47th Brigade, which included the 6th Connaught Rangers, was on the right, and the 49th Brigade was held in reserve. The attack was to be carried out in waves, and the 6th Connaught was assigned to the fifth and sixth waves. Their supporting artillery barrage, which preceded the assault, was completely ineffectual, leaving the German positions almost intact. In front of the 6th Battalion was a trench "hidden and believed innocuous", when in reality it had been "developed as the enemy’s main resistance" -- "a veritable hornets’ nest". The new battalion commander, Lt. Col. Rowland Feilding, describes the attack in War Letters to a Wife.

"We'll never come out alive, sir!", he answered.

The leading wave of the 47th Brigade, as I have said, left the trench at 4.47. It was immediately mowed down, as it crossed the parapet, by a terrific machine-gun and rifle fire, directed from the trench in front and from numerous fortified shell-holes. The succeeding waves, or such as tried it, suffered similarly.It was under this curtain of withering enemy fire that Sargeant John Thomas Cox was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM), a decoration for conspicuous gallantry in the field, and second only to the Victoria Cross. It was issued only to non-commisioned ranks, a very British nod to its class system, and a practice now, thankfully, abandoned. We read in the London Gazette (Suppl. 13 Feb 1917:1553):

His award was mentioned in the 1917 New Year's Honours List.

The tattered remnants of the 47th Brigade, were forced back to their trench. Francis Jourdain, Feilding's signals officer, declared: "The thing finished as a shambles", but only for the 47th Brigade. The 48th and 49th Brigades, fought on to storm, capture and hold Ginchy, effectively breaking the German line.

|

| source |

The 16th Irish Division had fought two battles in quick succession, without respite or reinforcement, and won, but at a harrowing cost. Too many of its officers and men were dead [vii], missing or wounded, and the survivors were exhausted. It was temporarily withdrawn from the line on the 10th of September 1916: bloodied, but unbowed.

The Division left the Somme and was transferred to West Flanders. The journey took two weeks. Leaving Ginchy, they marched to Corbie via Carnoy, were bused to Huppy, where they boarded a train for Bailleul, and then marched to their new camp at Locre (Loker) in Belgium. Here the 16th

would be rested and rebuilt with new clothing, equipment, manpower and training (particularly in the use of the new box respirator gas mask). On the 27th of September, they were moved to front line trenches on the Vierstraat and Spanbroekmolen Sectors, the area between Kemmel and Messines (Mesen), south of Ypres. At the time, these sectors were relatively quiet, allowing the new recruits time to become accustomed to the rigours of trench warfare. On the morning of the December 25th, 1916, the guns fell silent. John, and about five hundred other Rangers of the 6th Battalion, was at the ruins of Shamus Farm, located about 300 yards behind the front line. The men were on their knees in the mud, celebrating Christmas Mass. A young lieutenant, Charles Brett wrote: "It was the most impressive service I ever attended."[viii]

The first quarter of 1917 was routine, with its repetition of front line duty, relief, and reserve line tasks. At the front, it was tit for tat artillery bombardments, working parties to repair the damage done to the trenches and wire, sniping, patrols and raids. In reserve, it was parades, inspections, route marches, drill, weapons training and camp maintenance. Rest periods were allowed for bathing, religious services, listening to music played by military bands, cross-country races, inter-platoon football matches, and, in Irish regiments, even hurling. Then without introduction, between the 21st and 30th of April, we read in the 6th Battalion's War Diary that "this period was devoted, as much as possible, to the training of men for the attack". In the days that followed, training intensified. Then, in mid-May, the 47th Brigade was removed from the line, and transferred sixty kilometers westward to Bayenghem-lès-Seninghem. Here, it practiced the capture of Wytschaete, a fortified village on the plateau of Messines Ridge. On the Brigade parade ground, a replica of German trenches to the west of the village had been laid out for a "dress rehearsal" of the operation. In advance of the battle, John, now a veteran of the trenches, was promoted to Temporary Second Lieutenant. On the 29th of May, the Brigade was ordered back to the front, marching first to Arques, then Staple (on the 30th), and finally to Clare Camp, two miles west of Locre (Loker) (on the 31st), a distance of about 55 km.

Shock and Awe: The Battle for Messines Ridge

On the return of the 47th Brigade to the front, an intense artillery bombardment of the enemy's line had already begun. It would last for ten days: continuously, day and night, destructive, deadly and deafening. Over three and half million shells, gas cannisters, thermite bombs and oil-filled incendiaties pummeled German positions, wire and artillery batteries. A letter, written by a German soldier, was found on the ridge after the battle, and was dated 6 June 1917. It was addressed from "a shell hole in hell". It went on to say, "You have no idea what it is like. Fourteen days passed in hellish fire, day and night. ... we crouch together in holes and await our doom". One can only pity him, for doom would be delivered the next day. Unknown to the Germans, British sappers had mined beneath Messines Ridge, and planted some 450 tonnes of high explosives beneath the enemy's positions.

At 3:30 am on the 7th of June 1917, the men of the 16th Irish Division witnessed a scene straight from the Book of Exodus as huge columns of fire pierced the night sky. The subterranean mines had been detonated, but this was only the prelude to the combined effort of men, tanks and planes along a twelve mile front, all of which had been meticulously rehearsed and coordinated by General Plumer.

|

| Disposition of troops prior to the Battle of Messines |

|

| The Corridor of Operations for the 16th Irish Division Wytschaete is in the middle, on the Blue Line |

The 47th Brigade, under the protection of a creeping barrage, attacked up the western slope of the ridge, reached the Blue Line and secured their main objective, the capture of Wytschaete. This was accomplished by midday after some hard fighting, and the taking of a thousand prisoners. The commanding officer of the 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers, Lt. Col. Rowland Feilding, wrote:

After a bombardment without equal in history, we attacked the Germans yesterday at ten minutes past three, and took the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge. Our Brigade was allotted what was expected to be the most formidable task of the day - the capture of Wytschaete Village, which had been held by the enemy since 1914."

While the 6th Battalion was involved in "mopping up"and consolidating, a second wave of Irish troops crossed the ridge and advanced down the eastern slope to secure Oosttaverne, beyond the dotted black line on the map above, and beyond all expectations. The Germans had been deprived of the high ground, their morale had been damaged by the shockingly high death toll, and the front had been advanced by about two miles.

The Battle of Messines became symbolic in that nationalists of the 16th Irish Division and unionists of the 36th Ulster division fought side by side. The fallen are commemorated at the Irish Peace Park near Messines. One of the casualties was Major Willie Redmond. His last will and testament declared:

The success at Messines, with relatively few casualties, is largely due to Plumers' diligent planning and methodology. In the next chapter of the John's war, these crucial elements would be missing, and the consequences tragic. General Gough, commanding the Fifth Army, requested that the 16th Irish and 36th Ulster Divisions be transferred from Plumer's Second Army to his own command. Haig agreed. It was the kiss of death.

The decision to break out of the Ypres Salient in 1917 spawned one of the longest and bloodiest attrittional struggles on the Western Front. The basic mode of operation was called 'bite and hold', with gradual advances followed by consolidation. Over the ensuing months, this tactic would push the British front line to Passchendaele, just slightly over 11km north east from the Menin Gate at Ypres. The 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers fought in the first two 'bites', at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July-2 August) and at the Battle of Langemarck (16–18 August). During this period, the battalion operated under almost constant enemy artillery fire.

When the Battle of Pilckem Ridge began on the 31st of July, the Connaught Rangers were in reserve in the Brandoek area, west of Ypres. The next day, at 5:00 pm, they were given one hour's notice to move to the front. Not a good sign. They were assigned to the left of the Corps' front, relieving the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers. There they remained throughout the night. It rained incessantly, flooding the trenches. During the first day's fighting nearly 4,500 men were killed, and thousands more wounded. Consequently, on the 2nd of August, from 2am until 11am, 50 men from each company of the Rangers were lent to the 55th (West Lancashire) Division as stretcher bearers to recover the wounded now strewn about what was "the area covered by the old German front system". This was accomplished under extremely arduous and dangerous conditions.

The remainder of the battalion pushed on, under heavy shelling and in close support of the 6th Royal Irish, to the battle's first objective, the blue line, near Potijze. Shelling continued throughout the 3rd of August, and heavy rain continued to fall. To make matters worse, the following night, the Rangers were subjected to attack by Germany's new weapon, mustard gas. On the 6th of August, the battalion was relieved and returned to Brandoek. The battion's War Diary records:

After a period of 'consolidation', it was time for the second 'bite'. For the last time, the 36th Ulster and 16th Irish Divisions would fight together. After the Battle of Langemarck, only remnants would be left of either. The war correspondent, Philip Gibbs, declared, "The two Irish Divisions were broken to bits, and their brigadiers called it murder." He tells the harrowing story here and here. It was during the Battle of Langemarck that Father Willie Doyle, SJ, MC, chaplain with the 16th Irish, devout, and beloved of his comrades, was killed by a shell while ministering to the wounded.

The 6th Connaughts held the line until the night of August 17th, when the War Diary records: "The night Aug 17-18 marked the end of the active part played by the battalion in the third battle of Ypres. Total casualties during the whole period, 31 July - Aug 18, were 21 men killed and 2 missing, 4 officers and 205 other ranks wounded."

The Third Battle of Ypres would drag on until the 10th of November, for very little gain. In its later phase, it would become known as Passchendaele, a rat-infested charnel house of mud and murder and misery. If it was a victory, it was Pyrrhic. We still argue about the number of casualties...300,000? 400,000? 500,000? Who knows, but one thing is certain: the ill-managed Battle of Passchendaele was, and will forever be, a criminal disgrace.

Spared the worst of Passchendaele, the 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers was transferred from the Ypres sector, and moved by train to Bapaume, arriving at 2:00 am on the morning of the 23rd of August. Three days later, the remnants of the 16th Irish Division relieved the 21st Division near Bullecourt, about 22 km west of Cambrai. During October,the division would be rebuilt in preparation for its new objective, to capture a 2000 yard section of the "Tunnel Trench", which was part of the elaborate defences of the Hindenburg Line. Siegfried Sassoon, who saw the tunnel firsthand, described it as a "triumph of Teutonic military engineering". The attack was intended to serve as a diversion, while the Third Army, using mass tanks, air support, artillery and infantry, attacked Cambrai. The goal of the Battle of Cambrai was to break through the Hindenburg Line.

The plan was for the 16th Division to attack on the left, while the 9th Brigade of the 3rd Division would strike immediately north of Bullecourt on the right. From their front line, about 200 yards of No Man's Land had to be crossed before reaching the Tunnel Trench. Some 300 yards further on was a support trench. This sector was defended by about 2000 troops. The Tunnel Trench was thirty to forty feet underground, and an estimated 13 miles long, with a staircase every 25 yards. It was designed to facilitate communications and to house and protect men, supplies and ordnance. Reinforced concrete machine-gun pillboxes (Mebus), of the type that had decimated the 16th Division during the Battle of Langemarck, were placed along its defensive line. This lethal system had brought failure to an attempt to capture the Tunnel Trench during the spring of 1917. The Tunnel Trench was also mined with a failsafe system, which could be detonated if fell into enemy hands. Fortunately, during a raid in October, an engineer with the 7th Leinsters had noticed that the Tunnel Trench was mined. So, Royal Engineers of the 174th Tunneling Company accompanied the first assault wave and disabled the explosive charges.

Zero hour: 6:20 am on the 20th November 1917. It was overcast, with limited visibility, and there had been no preliminary bombardment, which might have signalled to the Germans that an attack was imminent. Instead, a smoke screen was laid in imitation of a gas attack, causing the enemy to don their gas masks and retreat underground. Then, just prior to the advance, the artillery initiated a four minute creeping barrage. The objectives of 6th Connaught Rangers were to secure the parapet, clear a section of the Tunnel Trench and immobilize Mars and Jove, two concrete pillboxes. Mars and Jove were assigned to B and A companies respectively. As the operation played out, it became obvious that the right flank of A Company was exposed. Elements of the 9th Brigade, on the right, attacked Bovis pillbox and the trench lying immediately north of Bullecourt.

It took the Rangers four and half minutes to cross No Man's Land, and secure their section of the Tunnel Trench without incurring any casualties. Once this had been accomplished, Mars and Jove were attacked from the rear, both surrendering with only slight resistance. At 7:10 am, the Germans counter-attacked in force on the exposed right flank, "bringing up an overwhelming superiority of men, bombs and ammunition through the tunnel from the South". Unfortunately, the plan to block the tunnel, to prevent this from happening, failed when the officer leading the tunnelers of the Royal Engineers was killed. Fierce hand to hand combat ensued, as the Rangers began to run short of ammunition. Fielding reported that, at a critical moment, 8006 Pte. K. White was catching German hand grenades in mid-air, and flinging them back upon the enemy before they exploded. "The men fought with the most heroic determination", he wrote. Captain Brett, in command of A Company was shot in the face, and all but two of his men were wounded. Holding the enemy at bay with a Lewis gun, they withdrew stubbornly to Mars. By 8.30, platoons from C and D companies were sent in to reinforce the Tunnel Trench. Three days later, Jove was re-captured by the 7th Leinsters, and the capture of the Tunnel Trench completed. The 6th Connaughts had lost 34 men, with 109 wounded.

The 16th Division was relieved by the 40th on the 2nd of December 1917, moved to a camp in Gomiécourt, and then proceeded south to hold a routinely quiet sector of the line near Lempire and Ronssoy, just to the east of Sainte-Émilie. The men were in festive mood on Christmas Day, and dinner was served in two large huts. Little did they know it would be the last Christmas of the war, and, for most, their last ever.

Reading through the War Diary of the 6th (Service) Battalion Connaught Rangers, we notice that volume 28 for March 1918 is missing. This is not the result of carelessness or accident. Its loss is symbolic of the disarray, dislocation and destruction caused by Germany's massive Spring Offensive, known as Kaiserschlacht, the Emperor's Battle, or the Ludendorff Offensive. It was Germany's last opportunity to win the war, before the full effect of America's intervention tipped the balance. Moreover, after the October Revolution, Russia sued for peace, and turned to civil war. This released some fifty divisions of the German Army, which were rapidly deployed to the Western Front, which happened to coincide with a reduction of British divisional strength due to manpower shortages. Germany's ultimate goal was to breach the front, outflank the British Army and seize the Channel ports, cutting off supplies. Quartermaster General Ludendorff had assembled 74 divisions, 6,600 field guns, 3,500 mortars and 326 aircraft to do the job. The first episode of Kaiserschlacht was called Operation Michael.

|

| source |

The Battle of Messines became symbolic in that nationalists of the 16th Irish Division and unionists of the 36th Ulster division fought side by side. The fallen are commemorated at the Irish Peace Park near Messines. One of the casualties was Major Willie Redmond. His last will and testament declared:

Mud, Misery and Mayhem

The decision to break out of the Ypres Salient in 1917 spawned one of the longest and bloodiest attrittional struggles on the Western Front. The basic mode of operation was called 'bite and hold', with gradual advances followed by consolidation. Over the ensuing months, this tactic would push the British front line to Passchendaele, just slightly over 11km north east from the Menin Gate at Ypres. The 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers fought in the first two 'bites', at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge (31 July-2 August) and at the Battle of Langemarck (16–18 August). During this period, the battalion operated under almost constant enemy artillery fire.

When the Battle of Pilckem Ridge began on the 31st of July, the Connaught Rangers were in reserve in the Brandoek area, west of Ypres. The next day, at 5:00 pm, they were given one hour's notice to move to the front. Not a good sign. They were assigned to the left of the Corps' front, relieving the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers. There they remained throughout the night. It rained incessantly, flooding the trenches. During the first day's fighting nearly 4,500 men were killed, and thousands more wounded. Consequently, on the 2nd of August, from 2am until 11am, 50 men from each company of the Rangers were lent to the 55th (West Lancashire) Division as stretcher bearers to recover the wounded now strewn about what was "the area covered by the old German front system". This was accomplished under extremely arduous and dangerous conditions.

|

| Stretcher-bearers knee deep in mud, August 1917 |

|

| Letter of Thanks from the 55th Division to Major-General Sir William Bernard Hickie, Commander, 16th Irish Division |

The remainder of the battalion pushed on, under heavy shelling and in close support of the 6th Royal Irish, to the battle's first objective, the blue line, near Potijze. Shelling continued throughout the 3rd of August, and heavy rain continued to fall. To make matters worse, the following night, the Rangers were subjected to attack by Germany's new weapon, mustard gas. On the 6th of August, the battalion was relieved and returned to Brandoek. The battion's War Diary records:

Thus ended a very arduous and trying tour in which the conditions had been as adverse as could be imagined. The weather was execrable and the ground a sea of mud. Trench foot was common. The men were almost continuously under fire without any opportunity of giving anything in exchange. But through all, and in spite of all, the spirit of the men was excellent and their behaviour could not have been better.

The 6th Connaughts held the line until the night of August 17th, when the War Diary records: "The night Aug 17-18 marked the end of the active part played by the battalion in the third battle of Ypres. Total casualties during the whole period, 31 July - Aug 18, were 21 men killed and 2 missing, 4 officers and 205 other ranks wounded."

|

| The Irish poet, Francis Ledwidge, was one of the 4500 men killed on 31 July 1917 |

The Third Battle of Ypres would drag on until the 10th of November, for very little gain. In its later phase, it would become known as Passchendaele, a rat-infested charnel house of mud and murder and misery. If it was a victory, it was Pyrrhic. We still argue about the number of casualties...300,000? 400,000? 500,000? Who knows, but one thing is certain: the ill-managed Battle of Passchendaele was, and will forever be, a criminal disgrace.

Assault on the Tunnel Trench

Spared the worst of Passchendaele, the 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers was transferred from the Ypres sector, and moved by train to Bapaume, arriving at 2:00 am on the morning of the 23rd of August. Three days later, the remnants of the 16th Irish Division relieved the 21st Division near Bullecourt, about 22 km west of Cambrai. During October,the division would be rebuilt in preparation for its new objective, to capture a 2000 yard section of the "Tunnel Trench", which was part of the elaborate defences of the Hindenburg Line. Siegfried Sassoon, who saw the tunnel firsthand, described it as a "triumph of Teutonic military engineering". The attack was intended to serve as a diversion, while the Third Army, using mass tanks, air support, artillery and infantry, attacked Cambrai. The goal of the Battle of Cambrai was to break through the Hindenburg Line.

|

| The Tunnel Trench of the Hindenburg Line in relation to Bullecourt |

|

| Reinforced concrete personnel shelters serving as machine-gun emplacements, and known in German as Mannschafts Eisenbeton Unterstände (MEBU). Some were named after Classical gods. |

The plan was for the 16th Division to attack on the left, while the 9th Brigade of the 3rd Division would strike immediately north of Bullecourt on the right. From their front line, about 200 yards of No Man's Land had to be crossed before reaching the Tunnel Trench. Some 300 yards further on was a support trench. This sector was defended by about 2000 troops. The Tunnel Trench was thirty to forty feet underground, and an estimated 13 miles long, with a staircase every 25 yards. It was designed to facilitate communications and to house and protect men, supplies and ordnance. Reinforced concrete machine-gun pillboxes (Mebus), of the type that had decimated the 16th Division during the Battle of Langemarck, were placed along its defensive line. This lethal system had brought failure to an attempt to capture the Tunnel Trench during the spring of 1917. The Tunnel Trench was also mined with a failsafe system, which could be detonated if fell into enemy hands. Fortunately, during a raid in October, an engineer with the 7th Leinsters had noticed that the Tunnel Trench was mined. So, Royal Engineers of the 174th Tunneling Company accompanied the first assault wave and disabled the explosive charges.

|

| Disposition of lead battalions for the attack on the Tunnel Trench |

Zero hour: 6:20 am on the 20th November 1917. It was overcast, with limited visibility, and there had been no preliminary bombardment, which might have signalled to the Germans that an attack was imminent. Instead, a smoke screen was laid in imitation of a gas attack, causing the enemy to don their gas masks and retreat underground. Then, just prior to the advance, the artillery initiated a four minute creeping barrage. The objectives of 6th Connaught Rangers were to secure the parapet, clear a section of the Tunnel Trench and immobilize Mars and Jove, two concrete pillboxes. Mars and Jove were assigned to B and A companies respectively. As the operation played out, it became obvious that the right flank of A Company was exposed. Elements of the 9th Brigade, on the right, attacked Bovis pillbox and the trench lying immediately north of Bullecourt.

It took the Rangers four and half minutes to cross No Man's Land, and secure their section of the Tunnel Trench without incurring any casualties. Once this had been accomplished, Mars and Jove were attacked from the rear, both surrendering with only slight resistance. At 7:10 am, the Germans counter-attacked in force on the exposed right flank, "bringing up an overwhelming superiority of men, bombs and ammunition through the tunnel from the South". Unfortunately, the plan to block the tunnel, to prevent this from happening, failed when the officer leading the tunnelers of the Royal Engineers was killed. Fierce hand to hand combat ensued, as the Rangers began to run short of ammunition. Fielding reported that, at a critical moment, 8006 Pte. K. White was catching German hand grenades in mid-air, and flinging them back upon the enemy before they exploded. "The men fought with the most heroic determination", he wrote. Captain Brett, in command of A Company was shot in the face, and all but two of his men were wounded. Holding the enemy at bay with a Lewis gun, they withdrew stubbornly to Mars. By 8.30, platoons from C and D companies were sent in to reinforce the Tunnel Trench. Three days later, Jove was re-captured by the 7th Leinsters, and the capture of the Tunnel Trench completed. The 6th Connaughts had lost 34 men, with 109 wounded.

The 16th Division was relieved by the 40th on the 2nd of December 1917, moved to a camp in Gomiécourt, and then proceeded south to hold a routinely quiet sector of the line near Lempire and Ronssoy, just to the east of Sainte-Émilie. The men were in festive mood on Christmas Day, and dinner was served in two large huts. Little did they know it would be the last Christmas of the war, and, for most, their last ever.

Kaiserschlacht oder Schlachthaus?

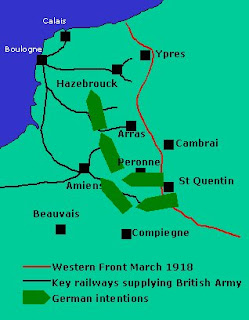

Reading through the War Diary of the 6th (Service) Battalion Connaught Rangers, we notice that volume 28 for March 1918 is missing. This is not the result of carelessness or accident. Its loss is symbolic of the disarray, dislocation and destruction caused by Germany's massive Spring Offensive, known as Kaiserschlacht, the Emperor's Battle, or the Ludendorff Offensive. It was Germany's last opportunity to win the war, before the full effect of America's intervention tipped the balance. Moreover, after the October Revolution, Russia sued for peace, and turned to civil war. This released some fifty divisions of the German Army, which were rapidly deployed to the Western Front, which happened to coincide with a reduction of British divisional strength due to manpower shortages. Germany's ultimate goal was to breach the front, outflank the British Army and seize the Channel ports, cutting off supplies. Quartermaster General Ludendorff had assembled 74 divisions, 6,600 field guns, 3,500 mortars and 326 aircraft to do the job. The first episode of Kaiserschlacht was called Operation Michael.

|

| One of the principal objectives of the Kaiserschlacht was the capture of Amiens, a strategic railway hub |

In the trenches, there had been rumours of an impending offensive. These were confirmed on the 21st of March 1918, when a five hour barrage delivered over three and a half million shells and gas along a 60 km front from La Fère to Quéant. It was the biggest artillery barrage of the war, and was aimed at Gough's Fifth Army, of which the 16th Irish Division was a part. In every respect, it was the wrong place at the wrong time, as the map below shows. The 16th Division was not in great shape either. It was tired, (the 6th Connaughts had spent 58 days at the front). It had been downsized. There were too few experienced officers left (even its commanding officer, Hickie, had been replaced), and the new drafts of men, though no longer Irish, were unfit and poorly trained. Facing them were six divisions of fresh troops. When the barrage stopped, the Germans appeared out of the thick morning fog like a tsunami. They were unstoppable. Within two days, the British line had been broken, with the Fifth Army in full retreat. But no one should question the bravery of the Irish soldier during this debacle. In the face of this overwhelming onslaught, the 6th Connaught Rangers received an order to counter-attack (with no artillery support), and they did .

By the end of the first day of Operation Michael, the 16th Division had suffered such losses that it was no longer a viable fighting force. Captain Staniforth wrote to his father: "The Division has ceased to exist, wiped off the map..." On the 31st July 1918, the 6th Connaught Rangers were formally disbanded. Many of its survivors were transferred to the 2nd Battalion Leinster Regiment, who had been equally mauled.

At some stage after Operation Michael, John Thomas Cox was sent to the 3rd Reserve Battalion Connaught Rangers, stationed in Dover. On 4 September 1918, he, along with Lieutenant J A Sheridan and 34 other ranks were dispatched to Palestine to join his regiment's 1st Battalion, part of the 7th Infantry Brigade of the 3rd (Lahore) Division, XXI Corps. This was in anticipation of General Allenby's Northern Offensive to drive the Ottoman Turks from Palestine, scheduled for the 19th of September.

The first phase of this offensive is called the Battle of Megiddo (1918). Megiddo is the biblical Armageddon, and the site of two major battles fought to block the expansion of ancient Egypt in the 15th century BC and in 609 BC. The site commands a narrow pass through the Carmel Ridge, part of an ancient trade route, which has always been strategically important.

On the 19th of September, the 3rd Division attacked on a 1800 yard front. The 1st Connaught Rangers moving northeastward toward Nablus. During the early morning, they overcame stiff resistance at Fir Hill, with its elaborate trench system, and went on to capture an artillery column at El Funduk. This was their final action of the war. On the 24th of September the 7th Brigade marched to Jenin, where they were garrisoned. The 1st Battalion Connaught Rangers later moved to

Nazareth, where John and many of his comrades were stricken by a particularly virulent form of malaria. On the 17th April 1919, he returned to his battalion, and "reported his arrival from sick leave, hospital and Palestine". He had miraculously survived three years of hard fighting in two theatres of war. The Catechism of the Catholic Church maintains: "Beside each believer stands an angel as protector."

John's medal card suggests that by 1921 he had returned to Midleton, Co. Cork. However, it may not

be too fanciful to state that at this particular juncture in history, when Ireland was fighting to free itself from the yoke of British imperialism, Irishmen, who had been in the service of the Crown, were not universally welcomed home. Their dilemma, after the Easter Rising of 1916, was that many of their own countrymen looked upon them with disdain, while, at the same time, they were treated with suspicion by the Army in which he served. Sir Roger Casement was adamant that Irish soldiers fighting in the British Army were not Irishmen, but English soldiers. Thomas Kettle, Irish Redmondite and Europeanist, wrote that the Rising had "spoiled it all - spoiled the dream of a free united Ireland in a free Europe", but he knew how he would be remembered.

Armageddon

At some stage after Operation Michael, John Thomas Cox was sent to the 3rd Reserve Battalion Connaught Rangers, stationed in Dover. On 4 September 1918, he, along with Lieutenant J A Sheridan and 34 other ranks were dispatched to Palestine to join his regiment's 1st Battalion, part of the 7th Infantry Brigade of the 3rd (Lahore) Division, XXI Corps. This was in anticipation of General Allenby's Northern Offensive to drive the Ottoman Turks from Palestine, scheduled for the 19th of September.

The first phase of this offensive is called the Battle of Megiddo (1918). Megiddo is the biblical Armageddon, and the site of two major battles fought to block the expansion of ancient Egypt in the 15th century BC and in 609 BC. The site commands a narrow pass through the Carmel Ridge, part of an ancient trade route, which has always been strategically important.

|

| The front line at 10 pm on the day before the Northern Offensive. The 3rd Division (3) (containing the 1st Connaughts) is positioned next to a weak right flank. source |

|

| Dotted red line is the old front. New dispositions at 10 pm on the first day of the Northern Offensive. |

On the 19th of September, the 3rd Division attacked on a 1800 yard front. The 1st Connaught Rangers moving northeastward toward Nablus. During the early morning, they overcame stiff resistance at Fir Hill, with its elaborate trench system, and went on to capture an artillery column at El Funduk. This was their final action of the war. On the 24th of September the 7th Brigade marched to Jenin, where they were garrisoned. The 1st Battalion Connaught Rangers later moved to

|

| Blue dot represent the location of Fir Hill. El Funduk is circled in blue |

|

| Part of the captured Turkish artillery column at El Funduk. 250 prisoners, six field guns, five mountain guns, two machine guns, 150 wagons, 250 animals and a large store of matériel were taken. The field gun records the date of capture 20.9.18 by "The Connaught Rangers" |

Nazareth, where John and many of his comrades were stricken by a particularly virulent form of malaria. On the 17th April 1919, he returned to his battalion, and "reported his arrival from sick leave, hospital and Palestine". He had miraculously survived three years of hard fighting in two theatres of war. The Catechism of the Catholic Church maintains: "Beside each believer stands an angel as protector."

be too fanciful to state that at this particular juncture in history, when Ireland was fighting to free itself from the yoke of British imperialism, Irishmen, who had been in the service of the Crown, were not universally welcomed home. Their dilemma, after the Easter Rising of 1916, was that many of their own countrymen looked upon them with disdain, while, at the same time, they were treated with suspicion by the Army in which he served. Sir Roger Casement was adamant that Irish soldiers fighting in the British Army were not Irishmen, but English soldiers. Thomas Kettle, Irish Redmondite and Europeanist, wrote that the Rising had "spoiled it all - spoiled the dream of a free united Ireland in a free Europe", but he knew how he would be remembered.

The leaders of the Rising, he commented, 'will go down in history as heroes and martyrs; and I will go down - if I go down at all - as a bloody British officer.The alienation and divided loyalties of Irish soldiers serving in British regiments during the First World War is poignantly conveyed in the plight of Willie Dunne, the central figure in Sebastian Barry's modern classic, A Long, Long Way. As Terence Denmam remarked in his book, Ireland’s Unknown Soldiers, these Irish veterans were consigned to "political No Man's Land".

We don't know how John Cox felt, or how he was received, when he returned home, but, before 1925, he moved to England. His regiment was disbanded in 1922, and its colours laid to rest in St. George's Hall, Windsor Castle. We next encounter John in Hartlepool, Durham County, where he married Jane Margaret Allen in March of 1925.[ix] Their known children are:

- Joan M. Cox born in Hartlepool Sept. 1925

- Sheelagh A. Cox born in Hartlepool June 1927

- Mary J. Cox born in Stockton-on-Tees Dec. 1928 (named after John's mother)

- Robert H. Cox died in infancy in Hartlepool Dec. 1929

- Antonia Margaret Cox born in Middlesbrough Sept. 1936 (named after John's father)

John's military career:

- private

- corporal

- sargeant DCM (1 Jan 1917) London Gazette 13 Feb 1917

- temporary 2nd lieutenant

- temporary Lieutenant 30 Nov 1918

Lt. (War Subs. Maj.) J. T. Cox, D.C.M. (94685), having exceeded the age limit of liability to recall, ceases to 'belong to the T.A. Res. of Offrs., 10th Aug. 1949, and is granted the hon. rank of Lt.-Col.

|

| medal card: World War I |

|

| 1914-1915 Star - British War Medal - Victory Medal |

Read On -

The Night Before Guillemont

Irish Valour at Ginchy Battle

The Battle of Messines

Notes

Thanks to Adrian Foley for discovering a photograph of John in a newspaper.

[i] An Currach Glas, meaning ‘The Grey Marsh’ and formerly spelled Curriglass. The village was originally an Elizabethan Plantation, and part of Sir Walter Raleigh's estate. It appears on the oldest estate map in Ireland, John White's 1598 map of Mogeely Estate (see detail below)

[vii] In just over a week’s fighting on the Somme in September 1916, the 6th Connaught Rangers lost 23 officers and 407 enlisted men (Denman, T. Ireland's Unknown Soldiers: the 16th (Irish) Division 1992:101.Irish Valour at Ginchy Battle

The Battle of Messines

Notes

[i] An Currach Glas, meaning ‘The Grey Marsh’ and formerly spelled Curriglass. The village was originally an Elizabethan Plantation, and part of Sir Walter Raleigh's estate. It appears on the oldest estate map in Ireland, John White's 1598 map of Mogeely Estate (see detail below)

|

| Shown as 'Curroglasse'. Even in 1598 the T-Junction existed. |

[ii] John's birthplace

|

| Leitrim Street, Cork, showing Walsh's Place |

|

| Walsh's Place, Georgian carriage arch |

|

| Map of Cork (1869) showing location of Walsh's Place with the yard undeveloped |

|

| Map of Cork (1892) with the yard developed |

|

| Map showing Walsh's Place and the position of No. 2. |

|

| 2, Walsh's Place, Leitrim Street 2 bedroom, terraced cottage, about 55 sq m. |

|

| Aerial photograph of Walsh's Place. |

[iii] List of Midleton Solicitors from Guy's Cork Almanac (1913:112)

Barry, William J 1909;

Dunlea, James, Main street 1874;

Moloney, John, Broderick street 1908;

Ronayne, Jerome J, Main street 1896;

Wallis, Thomas H Gardner, Main street (and Cork) 1888.

[iv] "... in regard of Irish recruiting:- The 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers is complete. They are going up to Dublin in a few days. (9 April 1915)

[v] The war diary of the 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers records four deaths from this attack.

[vi] the newspapers said, "If there was any fault, they progressed too fast, having no time to safeguard the ground gained..."

Dunlea, James, Main street 1874;

Moloney, John, Broderick street 1908;

Ronayne, Jerome J, Main street 1896;

Wallis, Thomas H Gardner, Main street (and Cork) 1888.

[iv] "... in regard of Irish recruiting:- The 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers is complete. They are going up to Dublin in a few days. (9 April 1915)

[v] The war diary of the 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers records four deaths from this attack.

[vi] the newspapers said, "If there was any fault, they progressed too fast, having no time to safeguard the ground gained..."

[viii] Sheehan, W. (2011) The Western Front: The Irishmen Who Fought in World War One

[ix] https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVZ5-2LJN (Jen Allen). Jane Margaret Allen: birth registered March 1902 (FreeBMD UK) https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2F8L-B1T