Early Lives – Erika

Erika left school when she was fourteen, at

about the time that the Second World War broke out. Until then, she wasn’t

really aware of the approach of war, but things soon changed. For a year she

had to work as a sort of ‘home help’ in a household. This was compulsory for

girls when they left school (boys had to work on the land for a year when they

left school). She went to the central registry and was assigned to a house. The

place where Erika worked was in the town, so she could return home at night.

The work was difficult and tedious, as it involved doing all the housework. The

person she worked for was not very nice. She was only fourteen at the time, and

received a pittance of about five Reichsmark per month.

After a year, Erika started to work in a

factory in the town. It manufactured light bulbs and employed many

people. The factory was a part of a complex which produced armaments. In the

war, they continued the production of light bulbs but other parts of the

complex were involved in secret war work. She earned about twenty Marks per week

and got on well with the other girls. They often had sing-songs during which

they would “sing their hearts out!” They also had social evenings.

Early Lives – Günter

Günter and Erika met for the first time on

the street. He had a pair of shoes under his arm, and he stopped her to ask for

directions to the shoemaker. In fact, he was right in front of the shoemaker,

but he didn’t realize this, being a stranger in the town. Erika’s first

impression was that he was a “nice boy!” That was during the summer of 1943.

They didn’t meet again until the Christmas

party in the factory, and they were engaged to be married soon afterwards.

Their marriage took place in Fürstenwalde (photos of the church) in February

1944. It was a simple affair, as would be expected during such difficult times.

Günter was home on leave at the time. After returning to his duties, he had

another period on leave before being posted to Italy. The couple had a son born

in December 1944 whom they named Bernd.

|

| Marriage of Erika and Günter |

Wartime Fürstenwalde

The war was very real for the inhabitants

of Fürstenwalde. There was an air-raid on the wedding day of Günter and Erika.

They were forced to spend their wedding night in the air-raid shelter. There

were many bombing raids, as it was a prime target area due to the proximity of

an airfield. Erika’s family had their own shelter in the yard, and they often

spent entire days within it. It was very difficult, but at least they got away

with their lives and their house was not damaged by bombs.

In 1945, the entire town was bombed out and

many people were killed. A few doors away from Erika, there was a woman with

ten children who all perished in one night. Erika could never forget that poor

woman. The next day, they went to see the ruins – they probably should not have

done so but curiosity got the better of them. There was a three month old baby

who was never found.

Günter’s mother lived alone in Berlin. She

was bombed out on three occasions. Her house was destroyed, so she arrived on

Erika’s doorstep in Fürstenwalde. “Please, let me in, I have nowhere to go to!”

She stayed for a few days before going to stay with her daughter.

|

| Fürstenwalde toward the end of World War II |

One-Man Submarines

Günter was involved with secret war work,

designing one-man, or ‘midget’ submarines. These submarines were about 14 feet

(?) long and were intended to perform the same sort of functions as

conventional submarines, but under the control of one man. Once they were

designed and built, they were brought to Italy. They were transported by

articulated lorries over the Brenner Pass in winter – a difficult journey.

Günter was initially in Venice, and was

then moved to Trieste before December 1944. He worked to perfect the

submarines. They worked well, but had nothing to shoot at! The war was well

advanced by that stage, and the allied invasion of France and Italy had begun.

Prisoner in Belgrade

The Americans took Günter in Trieste. The Americans did not care much about them,

and handed thousands of them over to the Russian army, who in turn gave them to

Josip Tito, who was emerging as the leader of post-war Yugoslavia.

Günter and his fellow prisoners were forced

to march to Belgrade, a distance of 330 miles. They had to march a fixed

distance per day, and those who could not were simply shot. Many died on the

way. Before they left Trieste, many of Günter’s comrades stole from wagons and

stores – they had two pairs of shoes, two uniforms, and were so packed with

provisions that they could barely move! Günter packed his rucksacks full of

cigarettes and butter, taken from the wagons, which he planned to use to

bargain with. The march took months. Many of their guards, Yugoslav partisans,

had bare feet. “They were a bunch of undisciplined layabouts, but they had the

guns so they were right!”

When they reached Belgrade, they were put

into camps and segregated by their proficiency in various fields. The Yugoslavs

were looking for specialists, and as Günter said, “The war is finished, we have

lost now, I may as well do the best I can, I could do with a good job!”

Accordingly he volunteered. He was still in good health despite the march.

Günter worked in a factory making central

heating units. He was skilled in electrical welding, and he showed them a few

things, as they did not have the faintest idea. Günter overcame his POW status

to become the foreman, in charge of the Yugoslav workers, most of whom were

Macedonian (?). The factory made flanges and big pipes. When the items were

tested successfully, they received extra rations.

Günter was in a separate group of about

twelve prisoners of war, who lived in an old house in a factory yard. The

prisoners fixed up the house so that they had bunks, central heating and a

shower. Most of the educated Yugoslavs spoke German, so there was no problem

communicating. They treated Günter reasonably well, but he knew of men who were

beaten half to death because they were obstinate or argued back. Günter said to

himself that he hated pain, so he co-operated!

Günter remained in Belgrade until November

1948, when he was released. Four of his fellow prisoners had to remain. The

director of the factory who stayed, and who was freed, depending on who was

needed. “If you filled your quota, you were free!” He returned home with

honours, and a recommendation from the factory that he was a good worker, and

he could go back at any time.

Russian Zone

Conditions in the factory at Belgrade were

luxurious compared to those in Fürstenwalde. At the end of the war the bombing

stopped, but conditions deteriorated when the Russians took over. There was very little food; certain items

were rationed while many things were simply not available. They had to beg,

borrow and steal to survive. The Russians were in control of everything,

including jobs and food, and treated the local people very badly. The streets

were renamed after Lenin and Stalin and the children had to learn Russian in

school. It was like a Russian colony.

Erika did not know where Günter was for a

year after the war ended. She heard nothing until a card arrived through the

Red Cross that he was alive and well. It was a relief after a year and half of

not knowing. After that Erika sent a card and they could write to each other.

Erika was still living with her parents.

They could get half a pint of milk a day for the baby and a couple of spoonfuls

of sugar. Everyone clubbed together to save all rations for the child. The baby

had dysentery and typhoid. He is very lucky to be alive today as he was

practically dying for the want of food.

This went on until 1948 when Günter came

home. He decided they would leave Germany the first chance they got as he could

see there was no future there and he would not work with the Russians.

Travelling was very restricted and everyone had to show their passport.

Günter came home to Germany in November

1948 and in the new year he got a job in a factory making conveyor belts.[2] The

factory worker was a learned man and was fond of Günter. He was a German and

had built the factory up from scratch. He did not want to work for the Russians

either and began a plan to escape.

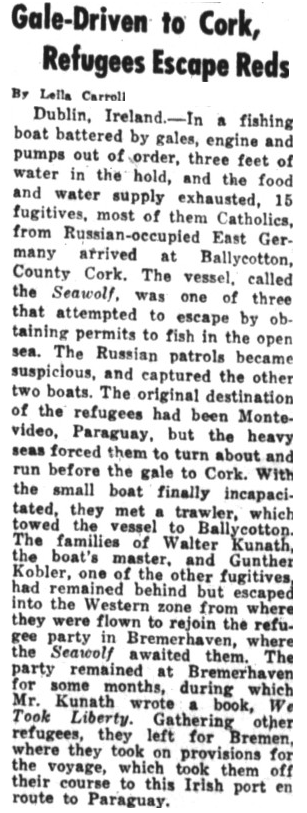

“See Wolf”

In the north of Germany on the Baltic coast is the island of Rügen. The town of Stralsund is nearby. The factory owner, Walter Kuneth, asked Günter to go to Rügen to work on rebuilding a 54’ yacht. Only the hull was in existence as the yacht had sunk during the war off the northernmost tip of the island. They didn’t know (or ask) who the hull belonged to, but it had been a luxury yacht before the war and had won a race from Germany to Australia. They renamed it See Wolf.

|

| See Wolf |

Günter was the main person working on rebuilding as he had naval experience. He was helped by men from the factory that went up a few times a week. The hull was towed to the village of Seedorf and rebuilt so that when completed it had 8 berths with a further two in the wheelhouse.

Erika and Bernd moved up to Stralsund while

Günter was working on the boat. They stayed for a while on a barge and in

lodgings. When the boat was finished they lived on board. They were there for a

good while.

|

| Cabin of the See Wolf |

In 1950, Erika was pregnant with Marion and when the baby was due Günter sent her and Bernd home to Fürstenwalde. The plan was that she would have the child there with her parents and return to Stralsund afterwards. The day after Marion was born, Erika’s mother sent a telegram to Günter but it came back marked ‘address unknown’. They were flabbergasted; they did not know where he had gone. Then they read about it in the papers that Walter Kuneth, his 2 sons (aged about 6 and 8) and Günter had escaped to West Germany. Erika knew nothing about it and had to read about it in the papers.

Escape to West Germany

When Erika was having Marion in

Fürstenwalde, the situation had deteriorated rapidly in Stralsund. The postman

came with a telegram for Walter Kuneth and the woman in the local pub phoned

him and told him that people were coming to look for them. The secret police

had been suspicious of them as they had been doing things to fix the boat which

were not “quite kosher”. As soon as he heard that they were being sought,

Walter said to start the engine as they would go. On board were his two young

sons Peter and Garth (?) and Günter. They started up and went along the coast

towards the Kiel Canal. They were pursued and shot at but were not stopped.

Once they reached the Kiel Canal they were safe as that was in West Germany.

They then went to Bremerhaven.

Meanwhile, Erika and her two children and

the skipper’s wife and daughter were all left behind. Erika was again left

alone! Günter sent her a secret letter through friends telling her to sell

everything and come. Erika did not know what to do at first. They had their own

flat by then. She sent bedding, blankets etc in parcels to Günter in

Bremerhaven. The postman might have gotten suspicious but at that time parcels

of bedding was not uncommon after the war. The authorities were not watching at

that time, but everything had to be kept secret.

Günter had given Erika a friend’s address

in West Berlin as a base for her to organise her escape. It took a lot of time and planning but Günter

had left money behind so she could live for the few months. Erika sent parcels

of possessions to Günter and also sold some clothes and other goods. She went

to Berlin and registered there in the American sector. She had to make regular

visits to West Berlin. Every day, early in the morning, she left the children

with her parents and went to Berlin on the first train. In West Berlin she got

her papers in order, arranged for a West German passport and sorted out various

details. She visited the British and American embassies. Everything was left

there and not brought back to the east. There were thousands of people wanting

to get out. It was easy enough to in and out of West Berlin, but everyone was

searched and questioned a lot. She would say she was going to West Berlin to

get food as they had everything there, including things like bananas and

oranges.

Eventually everything was ready in April

(?) 1951. Her parents brought her and the two children to the airport in Berlin

and she flew to Hamburg. It was the first time she had been on an aeroplane.

The stewardess came straight away and took Marion to where she would be

comfortable and she got a nice seat by the window.

The flight took about an hour. She felt

lonely leaving her parents behind. Her father was crying at the time,

particularly as they did not want Bernd to go. Erika kept in touch with her

parents until they died.

In Hamburg Günter was waiting for her. She

didn’t know whether to scold him or be glad! They were safe now, nobody could

touch them.

Bremerhaven

From Hamburg the family went by train to

Bremerhaven and lived on the See Wolf “like gypsies”. There were 15 of them on

board. Kuneth’s wife and daughter Rosemary had joined them and in addition

there were other adults.

The plan was to go to Uruguay in South

America where many Germans had settled after the war. The problem was that

money was needed for the journey and to establish themselves there. So it was

decided to sail there with See Wolf, using combined resources of the various

families and individuals. One girl, Anna, did not pay but in return was to cook

and clean etc for the others.

It was hard to live on See Wolf. Erika

wouldn’t do it again as it was too crowded and peope got on each other’s

nerves. They lived there for about a month after Erika arrived. They got ready

for the journey, enjoying the freedom to sail where ever they chose and to make

open preparations.

Most of the people on board were German who

were going to leave Germany anyway. Kuneth had advertised in the paper for

passengers, particularly for master tailors with their own sewing machines as

he planned to set up a factory in South America. There were 5 master tailors

and they all wanted to leave and all paid. There were 15 people in total, 5

children and 10 adults.

To sea in a “Nutshell”

One fine morning in May 1951, they left

Germany for good. Erika said “I will never forget it. I was standing on board

waving goodbye to Germany”. They planned to call to Dover, Cherbourg and

Falmouth before heading south to Spain and then across the Atlantic. Erika does

not think they would have ever made it as it would have taken 3 or 4 months and

water and food would have been a problem. “See Wolf was like a little

Nutshell”.

Günter was the only person on board who

could read a compass or a navigation chart. Early on everybody, including the

Skipper, was seasick – only Günter was able to sail the boat. Erika was very

seasick as she had never sailed before.

Dover was their first stop for fresh water

and food, but they were not allowed to land as feelings there were hostile to

Germans. They were barley allowed get food and water for the baby who was 4

months old by then. They did not stay long.

From Dover they went to Cherbourg where

they had a great time and took on more food and water. They people were very

friendly. Before they reached Cherbourg they had sailed half way up the Seine

to Paris because of a navigational error!

Falmouth was the next port of call – by

then Erika had had enough! They were welcomed there and the mayor gave them a

civic reception. See Wolf was lying beside big ships and the crews invited them

to take showers as they had no showers on board. They stayed there for a few

weeks because the weather was atrocious in the Bay of Biscay.

When they heard that the weather was good,

they set off to Vigo. They were in the middle of the Bay of Biscay when a huge

storm came up. They were terrified. They lost their sails, the dinghy, all the

charts and the engine broke down. Everything went wrong. The water came up in

the bunks and Erika thought that they were going to drown. The loss of the

charts meant that they were sailing “blind”. Erika thought it was the end. Günter

calculated on a school atlas belonging to one of the children that their only

hope was Ireland. So they drifted north.

|

Günter |

Ballycotton

The engine was broken so they just drifted

along. Nearly everyone was seasick including Erika who was very ill and could

barely look after Marion who had not been washed for weeks. They were very

short in food and water.

They drifted up and could see Ireland

faintly in the distance. Günter reckoned that they should arrive at Cork – this

was good reckoning as they were in fact just off Ballycotton. They were

wondering how they were going to make it in when up came the old Innisfallen

going to Swansea. They were delighted to see her and raised a flag asking for

help. The Innisfallen came over and with a loud speaker they asked what was the

matter. They said they were very glad to see her and asked them to organise

someone to pull them into harbour. Erika was so glad to see land! Everyone was

relieved.

Crowds gathered to watch them arrive. The

local people were swarming all over the place. The press were also there and

the photographs were taken of them all. The main attraction was Marion –

everyone wanted to see the East German baby! Erika put her on the pier and took

a photo of her. Later, Marion was out in the pram in the road and people kept

throwing money into her pram!

At Ballycotton they had to seek permission

to wash their clothes. They washed and washed and hung the clothes over the

pier – Erika wished she had taken a photo of it! It was a sight with the whole

pier full of clothes! People invite them into their homes and the house on the

corner (pub) invited them in and gave them a party. Local people were very good

to them and brought them eggs, milk for the baby etc. The Red Cross came and

brought them food too. They could not eat it all they had so much!

The priest came down and the bells were

ringing so he invited them to go to church. They did not know that Ireland was

a Roman Catholic country; in fact they knew nothing about Ireland. They went to

church on Sunday, although they were mostly Lutherans.

Only one of the group, Hans, spoke English.

He came from south of Germany, was a pilot during the war and had been a POW in

America so he spoke good English. He did all the interpreting. He was a master

tailor and made suits for everybody. Mr. Connolly of Ballycotton still had the

suit up to a few years ago! Hans later went to America and is now dead.

The group stayed in Ballycotton for about a

month and applied for asylum and within three days they had it. Günter and

Erika decided to stay – Erika refused to go any further! The others did not

want to stay permanently in Ireland. They were impressed by the Gardaí. The

Garda who came to see them was very casual, didn’t want to know any details and

said that they should receive asylum without any problem. He also brought Günter his first pint of

stout! No policeman would do that in Germany!

Günter had his first job in the harbour;

some fishermen asked him to fix an engine and paid him £5, which was a lot of

money then. They needed the money badly, but they wished they framed it as

their first earnings in Ireland!

Howth

In early July they sailed to Dublin. By

then the air compressor on the engine had been fixed but unfortunately it broke

down again in Wexford. Günter had to row to land and then walk to a garage to

get it fixed. The journey to Dublin was not too bad.

In Dublin they tied up at Butt Bridge and

people came down for sightseeing tours! They all wanted to see the baby. People

were very good and brought more food and money to enable them to buy napkins,

powder etc for Marion.

The group were all together then, but were

starting to get on each other’s nerves. They had had enough. Günter and Erika

said “they can do what they like, we will go our own way”.

The group stayed at Butt Bridge for a good

while before sailing to Howth. There they did some fishing with the boat and

sold the fish. They got a house up by the summit called “Wind Whistle”, beside

the tram station. It was very nice and romantic! The skipper and the Kohlers

shared the house which was quite big and had tow kitchens etc. The other in the

groups either slept in a summerhouse in the garden or on See Wolf.

The Kohlers came to know the area and were

treated well as people brought them vegetables and other gifts. Bernd, then

aged 6, started school (Howth National School) for the first time. He picked up

English very quickly. Maura and Eva O’Mahony from Howth were great friends and

kept in touch for years afterwards.

Dispersal

The Kohlers liked Howth and did quite well,

but the group continued to get on each other’s nerves from being together. They

had all different goals and ambitions. After a while the group split up and the

Kohlers went to Dun Laoghaire. They quickly lost touch and did not see any of

the group again.

Of those who arrived on See Wolf, some were

sent back to West Germany as they ran up debts in Ireland. The skipper tried to

“get rich quick” with suit making, but it didn’t work out and he became

discontented. His marriage broke up and he eventually went back to Germany. His

wife left with a Norwegian skipper. Another of the group died in Ireland. Hans

went to Canada and America. Anna married one of the men on board, Heinz (?).

They never heard anything more of the group. The Kohlers were the only ones to

remain in Ireland.

As for the See Wolf, it is said that she

was sold to somebody who went pearl fishing in the Caribbean. Maybe she is still sailing around!

Diving in Dun Laoghaire

Günter got a job as a diver in Dun

Laoghaire harbour, retrieving valuables which were on board a yacht which had

sunk in a storm. They family moved to a beautiful flat on York Road, owed by a

Mrs. Hutchinson (?) who was a very nice old lady. They paid £2.10 a week for

the flat which had a big drawing room, two bedrooms, kitchen etc. Bernd went to

school in Dun Laoghaire National School and Marion started walking.

After six or seven months the diving ended

and they were at their “wits end” to know how to survive. Günter could not get

a job in Dublin but heard of work in Cork. So “he swung himself on a bicycle”

and cycled all the way to Cork! It took about 5 days. Erika was left alone

again.

To the Funfair

Günter got work fixing the machines that

were used in Perk’s amusement park in Cork. He worked on the generators,

lighting and other mechanical aspects. He first worked at Perk’s near Victoria

Cross in Cork and then at their amusement park in Youghal.

When Günter was in Youghal he sent for the

family who travelled down by train. He got a room for them; it was peak season

in Youghal so there was very little available. The room was very poor compared

to their nice flat in Dun Laoghaire. Erika said it was like going from a castle

to a dungeon! However, the children had a marvellous time in Youghal. Every day

they went to the amusement park where they had rides for free and al the

ice-cream they could eat. Erika sunned herself on the beach, so it was a great

summer!

Wicklow

By the autumn, Günter’s job was over. By

then he had met a German who lived and worked in Wicklow town in a fertiliser

factory which was going to be built up.

He was looking for a top man to “run the show” and when he put the

proposition to Günter, he immediately accepted it.

Günter went to Wicklow and the family

followed. They stayed in Wicklow for 12 years and loved the place. It was their

real home. [1]

Günter was manager at Shamrock Fertiliser

which was owned by a Belgian, Mr. Vandenberg (?), who was very good to them.

They family first stayed in a little house by the harbour. One day, Mr.

Vandenberg came down and saw it and was horrified. He got them a lovely house

by the golf links, semi-detached, 3 bedrooms with all modern comforts. Erika’s

second daughter, Ingrid, was born here in 1954.

|

Erika, Ingrid, Bernd, Günter, Marion |

‘Sunnyside’

After some time they could afford a house. Günter’s

earnings started at £8 a week and rose to £20 a week. Günter bought a house in

Ashford for £1000. When they went to see it, Erika asked where the house was as

it was so overgrown by brambles, trees and all sorts of vegetation! It had not

been lived in for 8 years.

They soon got it fixed up and Günter got

help from factory workers to clear the garden. The workmen repaired the floors

and windows and it soon was a grand place: two bedrooms, sitting room, dining

room, kitchen, bathroom etc. It was on half an acre of land and had a lovely

apple orchard with it. They were “as happy as Larry” there.

They got their first car when living at

‘Sunnyside’. Günter also built a cruiser in Wicklow, buying as old hull and

building a cabin on it. It was used for pleasure and was called the Nomad.

Cork

In the 1960s, the fertiliser factory was

taken over by Gouldings and Günter had the option of remaining in Wicklow or

going to Cork where they were looking for a top man. It was decided to move to

Cork.

It was terrible selling the house as they

had put their hearts into it. The children were all settled in school and the

Kohlers really liked the area. However, they moved to Cork in 1966 and Ingrid

started in Ashton Grammar School. They bought a bungalow on Tramore road, Günter

worked in Gouldings and everything was fine. The only problem was Marion who

had been very ill at about this time with a tumour on the hip. She was in and

out of hospital, but fortunately got better and had a lot of treatment in the Orthopaedic.

The family remained in Cork from that time.

It was a long way in distance and time from the meeting outside the shoe

maker’s shop in Fürstenwalde!

RTE Radio Broadcast featuring Günter (Timeless 21 June 1991.

"Gunther Kohler pursed his education as an engineer by joining the German Army as a U-Boat sailor in 1941. He was captured by the Americans and sent to Russia and then Yugoslavia until his release in 1948. Gunther's Wife Erika had not seen him in years since their marriage and birth of their son. His unhappiness with the occupation of Germany by Allied forces, they decided to leave for Ireland after the birth of their second child. He left his wife and family and sailed towards South America, but after a storm ended up in Ballycotton in Co. Cork. Erika joined him later to make a new life in Ireland."Births

Bernd Jurgen Kohler was born on 15 December 1944.Death Notices:

KOHLER, Erica Cork COR IRL; Irish Examiner; 2000-12-4; KOHLER, Gunther; ; Cork COR IRL; Irish Examiner; 2001-3-9